The Cantor Set

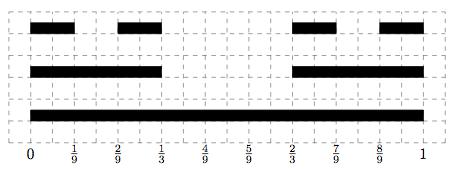

Consider the unit interval in the real line, \( [0,1] \), and remove the middle third open subinterval \( (1/3, 2/3) \). We have the closed set \( C_1 = [0,1/3] \cup [2/3,1] \), which is the union of two closed intervals. In a second step, remove the middle third open subintervals of each of the previous two intervals in \( C_1 \), to obtain the closed set \( C_2 = [0,1/9] \cup [2/9,1/3] \cup [2/3, 7/9] \cup [8/9,1] \).

The image below illustrates this procedure with the three sets constructed so far.

We iterate this procedure, thus constructing on each step a new closed set \( C_n \) by removal of middle third open subintervals from the previous set \( C_{n-1} \). Equivalently, the operation can be described as: take the union of the previous set, with a shift of it by two units, and scale them down by one-third. We can write then \( C_{n+1} = \frac{1}{3} \big( C_n \cup (2+C_n) \big) \) for each \( n \in \mathbb{N}. \) Notice that \( C_{n+1} \subset C_n. \)

This process is permitted to continue indefinitely. At the limit, we have removed from the unit interval a countable number of open subintervals; therefore, the resulting set \( \mathfrak{C} = \cap_{n \in \mathbb{N}} C_n \) must be closed. This is what we call the Cantor set.

Structure of the Cantor set

Empty?

Notice that the Cantor set is not empty: the numbers \( 0 \), \( \frac{1}{9} \), \( \frac{2}{9} \), \( \frac{1}{3} \), \( \frac{2}{3} \), \( \frac{7}{9} \), \( \frac{8}{9} \) and \( 1 \) all belong in \( \mathfrak{C} \). As a matter of fact, if \( x \in \mathfrak{C} \), then either \( 3x \in \mathfrak{C} \) or \( 3x-2 \in \mathfrak{C}, \) (or both!) which indicates that there are infinitely many elements in the Cantor set. We will use this fact below.

Measure

Let us measure the Cantor set: The unit interval measures one unit. In the first step, we have removed a subinterval of size \( \frac{1}{3} \); hence, \( C_1 \) measures \( 1 - \frac{1}{3} = \frac{2}{3} \). In the second step, we have removed from \( C_1 \) two subintervals of size \( \frac{1}{9} \); hence \( C_2 \) measures \( 1 - \frac{1}{3} - \frac{2}{9} = \frac{4}{9} \) units. In the \( n \)th step, we remove from \( C_{n-1} \) as many as \( 2^{n-1} \) subintervals of size \( \frac{1}{3^n} \); therefore, the size of \( C_n \) is \( 1 - \sum_{k=1}^n \frac{2^{k-1}}{3^k} \) units. At the limit, the Cantor set has therefore size

How is that possible?

Cardinality

By definition, \( z \in \mathfrak{C} \) if and only if \( z \in C_n \) for all \( n \in \mathbb{N}. \) This means, in particular, that we can find \( x \in [0,1] \) such that for any \( n \in \mathbb{N} \), there will be an \( n \)–tuple \( (\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \dotsc, \lambda_n) \) with \( \lambda_k \in\{0,2\} \) satisfying

Equivalently, for each \( z \in \mathfrak{C} \) and any \( \varepsilon > 0 \) there is some \( N=N(z,\varepsilon) \in \mathbb{N} \) and an \( N \)-tuple \( (\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \dotsc, \lambda_N) \) with \( \lambda_k \in \{0,2\}, \) such that \( \big\lvert z - 3^{-N}\sum_{k=1}^N 3^{k-1}\lambda_k \big\rvert < \varepsilon. \) It should be no trouble to prove that this property defines every element of the Cantor set.

For example, consider the sequence \( \{ \lambda_n \}_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \) with \( \lambda_{2k}=2 \) and \( \lambda_{2k+1}=0 \) for all \( k \in \mathbb{N} \). The sequence of partial sums \( x_n = 3^{-n} \sum_{k=1}^n 3^{k-1}\lambda_k \) is convergent, with \( \lim_n x_n = \frac{3}{4}. \)

Indeed, notice that

We have them proven that \( \frac{3}{4} \) is in the Cantor set, although it is not the endpoint of any of the removed subintervals in the original construction!

This is an alternative way to describe all numbers in the Cantor set:

\( z \in \mathfrak{C} \) if and only there exists a sequence \( (\lambda_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \) with \( \lambda_n \in \{0,2\} \) for all \( n \in \mathbb{N} \), such that the partial sum sequence \( x_n = 3^{-n} \sum_{k=1}^n 3^{k-1}\lambda_k \) converges to \( z. \)

We will use this description to construct an injective map \( \phi \colon [0,1] \to \mathfrak{C}, \) thus proving that the cardinality of the Cantor set is the same as that of the unit interval (and therefore, the Cantor set is uncountable!)

Let us use the density of dyadic fractions: for each \( x\in [0,1) \) and \( \varepsilon> 0 \), find a dyadic number \( d_{k,n}=k2^{-n} \) with \( k \in \{0,1,2,\dotsc, 2^n-1\} \) such that \( \lvert x-k2^{-n} \rvert < \varepsilon. \) We write \( k \) in its (unique) base-two expression as \( k=\mu_0 + 2\mu_1+ \dotsb + 2^{n-1}\mu_{n-1} \) with values \( \mu_j \in \{0,1\} \) for all \( j\in \{0,1, \dotsc,n-1\}. \) It is then \( d_{k,n} = 2^{-n}\sum_{k=1}^{n-1} 2^k\mu_k. \)

A similar reasoning as above shows that any number in the unit interval can be realized as the limit of a partial sum of a sequence \( x_n = 2^{-n} \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} 2^k\mu_k \) for a sequence \( (\mu_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \) satisfying \( \mu_k \in \{0,1\} \) for all \( k \in \mathbb{N}. \) We construct the function \( \phi \colon [0,1] \to \mathfrak{C} \) as follows: