Borsuk-Ulam and Fixed Point Theorems

At any given moment on the surface of the Earth there are always two antipodal points with exactly the same temperature and barometric pressure. We can go even further: on each longitude (the North and South lines running from pole to pole) there will also be two antipodal points sharing exactly the same temperature. How is this possible? The answer is given by the Borsuk-Ulam Theorem: a powerful tool in Topology with a great deal of applications to every branch of science.

A continuous function \( f\colon \mathbb{S}_{d} \to \mathbb{R}^d\) from a \( d \)-dimensional sphere into the Euclidean space of dimension \( d \) maps some pair of antipodal points \( \pm \xi \in \mathbb{S}_{d} \) to the same point \( \boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d. \)

The implications of this Theorem are huge. Some of the most useful are cited below:

- No subset of \( \mathbb{R}^d \) can be homeomorphic to a \( d \)-dimensional sphere \( \mathbb{S}_{d}. \)

- If we cover the sphere \( \mathbb{S}_d \) with a family of \( d+1 \) open sets, then at least one of these sets must contain a pair of antipodal points \( \pm\xi. \)

But the most useful application of Borsuk-Ulam is without a doubt the Brouwer Fixed Point Theorem.

Every continuous function \( f\colon K \to K \) from a convex compact subset \( K\subset \mathbb{R}^d \) of a Euclidean space to itself has a fixed point.

The proof of Brouwer Fixed Point from Borsuk-Ulam is immediate, and I urge the readers to find it by themselves as a nice exercise. There are many different proofs of Brouwer Fixed Point without Borsuk-Ulam, the simplest of them all, done by C.A.Rogers as a simplification of a previous proof by J.W.Milnor: it uses the most basic of mathematics, accessible to students with knowledge of elementary integral Calculus.

A version of this proof starts by showing that there are no differentiable maps with continuous derivative, from a closed ball to its border, that fixes all points in that sphere:

Let \( B_d\subset \mathbb{R}^d \) denote the unit ball in the Euclidean \( d \)-space, whose border is the \( (d-1) \)-dimensional sphere \( \mathbb{S}_{d-1}. \) There is no \( C^1 \) map (once-differentiable with continuous derivative) \( f\colon \overline{B_d} \to \mathbb{S}^{d-1} \) such that \( f(x) = x \) for all \( x \in \mathbb{S}_{d-1}. \)

The use of the previous result together with the Stone-Weierstrass Theorem guarantees the existence of fixed points for any continuous function \( f\colon \overline{B_d} \to \overline{B_d}. \)

Indeed, the Stone-Weierstrass Theorem gives the existence, for each \( n\in \mathbb{N}, \) of a polynomial \( P_n\colon \overline{B_d} \to \mathbb{R}^d \) satisfying \( \lVert f-P_n \rVert_2 \leq \tfrac{1}{n}. \) Consider the sequence of functions \( h_n(x) = \tfrac{n}{n+1}P_n\colon \overline{B_d} \to \overline{B_d}, \) which converges uniformly to \( f. \)

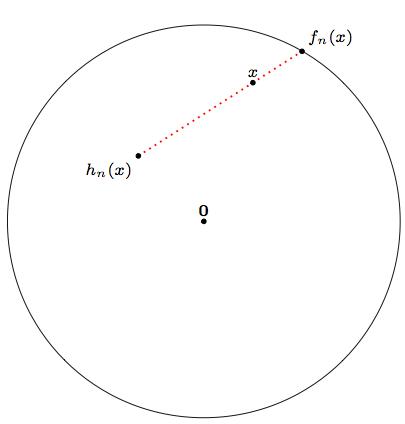

We claim that each function \( h_n \) has a fixed point \( x_n \in \overline{B_d}, \) \( h_n(x_n) = x_n. \) If this were not true, we would be able to construct \( C^1 \) functions \( f_n\colon \overline{B_d} \to \mathbb{S}_{d-1} \) satisfying \( f_n(x) = x \) for all \( x \in \mathbb{S}_{d-1}. \) Such a construction could be as follows:

|

If \( h_n \) has no fixed point, then it is possible to draw, for each \( x \in \overline{B_d} \), a ray through \( x \) emanating from \( h_n(x) \). This ray intersects \( \mathbb{S}_{d-1} \) at a single point, which we denote \( f_n(x). \) The function \( f_n\colon \overline{B_d} \to \mathbb{S}_{d-1} \) thus defined is \( C^1 \) and satisfies \( f_n(x) = x \) for all \( x \in \mathbb{S}_{d-1}, \) contradicting the previous result. |

This implies, as we announced before, the existence of a sequence of points \( x_n \in \overline{B_d} \) satisfying \( h_n(x_n) = x_n. \) The compactness of \( \overline{B_d} \) guarantees a convergent subsequence \( \big( x_{n_r} \big)_{r \in \mathbb{N}} \). Let \( x_0 \in \overline{B_d} \) be its limit. It must be then

and we have just found a fixed point for \( f. \)

The proof of the Theorem for continuous functions \( f\colon K \to K \) for a given convex compact set \( K\subset\mathbb{R}^d \) is done through an appropriate homeomorphism \( \varphi\colon B_d \to K. \)

Miscellaneous

Note that the Brouwer Fixed Point Theorem is not constructive: although the proof indicates how to come up with a fixed point, there is no explicit construction that finds such point. The key here is the Stone-Weierstrass Theorem, that claims the existence of a sequence of polynomials, but does not compute them.

We can find nonetheless a constructive version of a Fixed Point Theorem in the field of Analysis: the Banach Fixed Point Theorem. This result gives a general criterion that guaranties that, if satisfied, the procedure of iterating a function will yield a fixed point.

Let \( (X, \lVert \cdot \rVert) \) be a non-empty complete metric space. Let \( T \colon X \to X \) be a contraction mapping on \( X \), i.e.: there is a nonnegative real number \( q < 1 \) such that

\begin{equation} \lVert T(x) - T(y) \rVert \leq q\lVert x-y\rVert \text{ for all } x,y \in X. \end{equation}

for all \( x, y \in X. \) Then the map \( T \) admits one and only one fixed point in \( X. \) Furthermore, this fixed point can be found as follows: start with an arbitrary element \( x_0 \) in \( X \) and define an iterative sequence by \( x_n=T(x_{n-1}) \) for \( n \in \mathbb{N}. \) This sequence converges, and its limit is the fixed point of \( T. \)

Other versions also allow us to count how many fixed points will be for a given function. That is the case of both the Lefschetz and the Nielsen Fixed Point Theorems.